TWELVE

The Serpent’s Egg

By the end of 1932, at the age of twenty-six, Ettore had become a mature scientist in the eyes of the establishment. He’d finished his libera docenza37; had written groundbreaking papers in atomic, nuclear, and particle physics; and was internationally renowned. A generous grant of 12,000 lire, personally signed by Marconi, was awarded to him (for comparison, a full professor earned about 25,000 lire per year). Ettore was fast becoming famous. He even joined the Fascist party.

For the record, by 1933 everyone at Via Panisperna, with the sole exception of Corbino—who had other strings to his bow—was a party member. It was a mere formality, handy for cutting through red tape and when applying for state jobs or obtaining grants. Fermi joined in 1929; Ettore’s Zio Quirino in 1926; Lo Surdo—the only one who was a real Fascist—in a record 1925. Even Giulio Racah from the Florence group (later to emigrate to Israel and found physics there) was a member. Ettore wasn’t in the country when the relevant paperwork was signed, suggesting that he sent someone (his brother Salvatore?) to impersonate him. Like everyone else, he wore the Fascist party pin in his lapel, yet “every first of January he made a bet with a friend that before the end of the year Mussolini would be thrown out. And at the end of the year, at San Silvestre, he’d pay up the lost bet,” according to Maria.

Grant in hand, Ettore journeyed to Leipzig in January 1933 to join the Physics Institute. Which meant Heisenberg—his scooper and savior. And then a miracle happened. Ettore’s social reticence, his difficulties with dialogue and friendship, completely dissipated. Reading his letters and pooling recollections from others, we find him incongruously upbeat, positive, open to all. “At the Institute I’ve been received very cordially,” Ettore wrote to his family in January 1933. “I had a long conversation with Heisenberg who is a person of extraordinary courtesy and sympathy. I’m in excellent relations with all, particularly with the American Inglis whom I already knew from Rome and who keeps me company and often plays the guide. . . . The climate is pleasant . . . and life isn’t expensive. The numerous cafes and nightclub venues are good value, with great music and carnival-style happiness, brimming with people every Saturday evening. . . . The Institute of physics . . . is located at a pleasant location, slightly out of hand, between the cemetery and the madhouse.”

He went to the cinema, plunged into the nightlife, found the town comfortable and its people welcoming. Contrary to his habits, he even bothered to publish his work: “I’ve written an article on nuclear structure that pleased Heisenberg a great deal, even though it corrected his own theory. I’ll also publish in German an expanded version of my last article in ‘Nuovo Cimento’; in this paper one can find an important mathematical discovery, as it has been confirmed to me. . . .” He’s referring to his 1932 masterpiece, notably proud of his achievement, parading it around Leipzig, for once sensitive to praise and recognition.

The miracle was accomplished by none other than Heisenberg, who was then only thirty-one but already a full professor, famous for the discovery of his “uncertainty principle” and the mathematical framework of quantum mechanics. Heisenberg led a hedonistic lifestyle: He drank liberally and was an unabashed playboy; he played the piano exquisitely (if rather extravagantly) and was a top-class dancer; he was a recklessly speedy skier, always going off to the mountains in search of a good time. Heisenberg invariably woke up late and worked only in the afternoon: He claimed he could only do physics if he was enjoying life.

In keeping with his lifestyle and personality, Heisenberg kept things informal and lighthearted at his institute, but without the foolishness of Via Panisperna. He had a Ping-Pong table installed in the library, and much time was spent playing rather than working. But unlike Fermi, Heisenberg was highly cultured and could also be a deep thinker. His father was a classicist, and Heisenberg had been educated in that tradition, reading Plato and Aristotle’s major works in the original Greek. He had strong humanistic leanings and besides cutting-edge physics, philosophical discussions were part of the work schedule at his institute.

Together with Niels Bohr—his mentor and the founding father of quantum mechanics—Heisenberg was concerned with the ontological implications of the new theory. According to the most direct interpretation of quantum theory (to this day controversial), the world can happily live in superpositions of opposites until an observation is made, forcing reality to collapse into a solid certainty. The old philosophical threat of “reality as a projection of an individual mind”—or solipsism—had broken into science. Some of Heisenberg’s early works are a mixture of physics and philosophy, addressing the issue of solipsism very closely.

This was precisely the side of quantum mechanics Fermi could never understand, but which appealed so much to Ettore. His discussions with Heisenberg must have covered everything from neutrons to philosophy and literature. He wrote of Heisenberg in his early 1933 letters: “We have became great friends after many a conversation and some chess matches.” And “[Heisenberg’s] company is irreplaceable for me.” So complete was their rapport that they became a threat to everyone else, particularly during seminars, where they ganged up on critics of their strong nuclear-force theory. It seemed that Ettore had found a twin soul. And this probably explains why he became so outgoing.

But the revolution in his life extended beyond his relations with colleagues. He reported home that he was in good health, even though he drank liters of coffee and chain-smoked throughout this period of intellectual ebullience. On his own, without his mother, he dealt well with “life on a practical level,” to use Ettore Jr.’s turn of phrase. In his letters to his parents he notes and comments on the financial crisis that followed the Great Depression in America, expertly changing his lire as most appropriate, given the general volatility in the exchange markets. He became a man of the world, and it was through his diligence (by introducing him to an Italian employer) that his sister Rosina’s future husband, Werner Schultze, came to Rome. The escalating German political situation, mounting all around him, didn’t pass unnoticed to Ettore, either.

The interesting timing of Ettore’s sojourn in Germany has probably not escaped you. Barely a week after Ettore’s arrival, following a protracted political crisis, Adolf Hitler was nominated chancellor of the Reich. The gears were set in motion. It would have been difficult to ignore what happened next—even at an institute of physics.

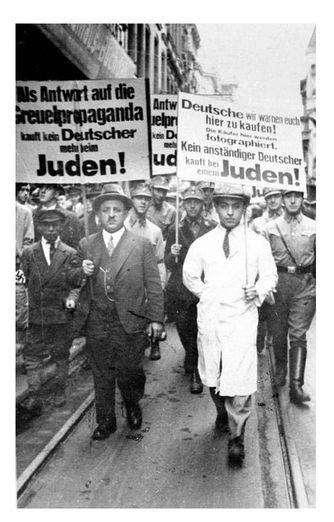

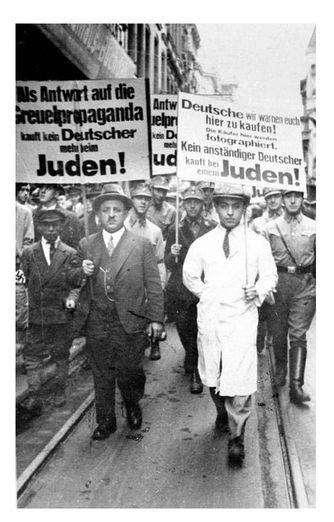

On the night of February 27, the Reichstag fire took place, an obvious act of arson that destroyed the German parliament. On the surface, this seemed to be a Communist plot, but it was actually a bit of theater orchestrated by Nazi storm troopers. Like modern terrorism (real or perceived), the fire gave Hitler the perfect excuse to suspend individual freedoms and assert his rule. On March 5, rigged elections gave a majority to the Nazis, who passed the Enabling Act on March 24, transferring full powers to Hitler. All opposition was ruthlessly destroyed in a series of purges that led to the establishment of the first concentration camps. Racism and anti-Semitism became widespread and part of the state ideology. March 31 was declared National Day of Boycott of the Jews, when storm troopers beat up or killed prominent Jews and those who engaged in business with them. On May 10, a large group of Nazi students congregated outside Berlin University to burn 20,000 Jewish books. “These flames not only illuminate the end of an old era, but shed light on the new one,” said Goebbels, the state ideologue. Jewish composers, and writers like Thomas Mann and Eric Maria Remarque, came under attack. And physics would not avoid the line of fire.

Boycott of the Jews demonstration. In this picture German Jews were made to march carrying signs stating “A good German doesn’t buy from the Jews,” and the like. The men in uniform are SA.

Strong credence was suddenly given to a movement called Deutsche Physik, which for years had attempted to establish the concept of Aryan—as opposed to Jewish—science. The movement was headed by two Nobel laureates, Johannes Stark and Philipp Lenard, and at best it was a critique of theoretical physics in favor of experimentation, at worst a mere smokescreen of racism and forceful interpretations. Unsurprisingly, their prime target was Albert Einstein: They condemned his theory of relativity as “the great Jewish bluff.” Einstein chose at first to ignore rather than respond to their attacks, but by 1933 he was forced to emigrate to the United States.38

Although Heisenberg was a staunch right-wing nationalist with undeniable “Aryan” credentials (he’d been part of the German Youth movement, for example), he wasn’t a moron, and all this nonsense against the theory of relativity irritated him. He opposed Deutsche Physik and was soon dangerously high up in their bad books.39 A public political argument broke out as to how the scientific interests of the Third Reich could best be served; the Deutsche Physik mob called Heisenberg a “white Jew,” providing a sense of the level of the debate. The early squabbles of 1933 would erupt into a full confrontation over the succession of the main professor in Munich (Arnold Sommerfeld), in what would become known in Nazi Germany as the “Heisenberg affair.” Heisenberg stood his ground, suffering heavily from his anti-Deutsche Physik stance. Who knows where his mind was while he discussed physics and philosophy with Ettore.

Perhaps so as not to alarm his family, Ettore refrained at first from commenting in his letters on the political incidents. He only mentioned hearing gun reports in Leipzig on the night of the fire, months after the fact. It wasn’t until May of 1933 that his letters began to reflect his views on the subject. We will examine these letters in detail, for the role they played in his personal tragedy. Because it was in one of his letters commenting on Nazism that Ettore did something “downright inexcusable” to Emilio Segrè.

As March 1933 approached and German academia broke up for Easter, Ettore moved on to Copenhagen. He liked the town a lot less than Leipzig but was still in high spirits as he joined the Niels Bohr Institute. He commented, tongue in cheek, in a letter to his father: “[Bohr is] the great inspiration of modern physics, now a bit aged and considerably senile. He still passes for a deep thinker; he speaks a jumble of all languages swallowing his words, giving the impression that if he bothered with his elocution other people might actually understand what he’s saying. Everyday he writes one word for his new article, which everyone is certain will be of decisive importance.”

Unlike relativity, which came to the world in one piece by the grace of the great Albert, quantum mechanics was a collective and multistage effort involving two generations. The early stages were the work of Max Planck, Albert Einstein (in his spare time), Prince Louis de Broglie, and, above all, Niels Bohr. Bohr also acted as a pivot to the second generation and the final formulation of the theory, as proposed by Heisenberg, Schrödinger, Dirac, and Pauli. So productive were those days that there weren’t enough Nobel Prizes to go around. Heisenberg won the 1932 Nobel Prize, but lest it might cause offense to his equally deserving competitors, this was only announced in November 1933, at the same time the 1933 Nobel Prize was awarded to Schrödinger and Dirac.

Niels Bohr was a national hero in Denmark and physically “looked as if he had absconded from the captaincy of a herring trawler,” in the words of Graham Farmelo. Bohr had been a talented football player (dispelling the myth that all footballers are stupid40), and like most of the quantum-mechanics pioneers was a heavy drinker (Dirac and Ehrenfest were the exceptions). By 1933 he was generally regarded as the father figure of quantum mechanics, attracting funding to the field and arbitrating disputes, providing worldwide leadership. He was thus the perfect target for cynicism and sarcasm à la Ettore Majorana. A leader just had to be a senile old fart, according to Ettore.

But Ettore did warm up to Bohr as he grew to know him better, acknowledging his good nature, if not his intellect. He wrote to Gentile to describe how Bohr had invited him to his home, which, like the Copenhagen Institute, was paid for by Carlsberg (as in “probably the best beer in the world”). The house was surrounded by such mountains of kegs that Ettore couldn’t find the entrance—he needed Bohr’s assistance to find the path through the beer labyrinth. Parenthetically, I note that much of the early research on quantum mechanics was sponsored by Carlsberg—a non-profit-making foundation. Spot how its bottles sneak into many historical photos. (One wonders if the most abstruse aspects of quantum mechanics, like the lack of determinism and the wave nature of matter, have deep roots in ethylization.)

Bohr’s institute was the center of quantum-mechanics research in those days, and Ettore had a chance to interact with its luminaries. He met the very rude Pauli, but did not seem to notice the hiccups and complaints reported by others (“a tipaccio , very nice and intelligent” was his verdict). He met the Dutch physicist Paul Ehrenfest, who inquired at great length about his work, inviting him to Leiden later in the year. This visit would never take place. Ehrenfest—a very intimate friend of Einstein—suffered from severe depression, and in September 1933 shot his younger son (who suffered from Down’s syndrome) before killing himself. But in the conversations between Ettore and Ehrenfest, there was no hint of dark thoughts from either side. The things that people think but don’t mention.41

Later, Bohr left for a brief stint in the mountains with Heisenberg, where the two often retired to discuss philosophy. They were both deeply concerned with the interpretation of quantum theory. They spent their breaks trekking and mountaineering, all the while racking their brains up in the snowy summits, trying to understand the deep meaning of the new science. “When [Bohr] returns he will resume the apostolate to spread the Spirit of Copenhagen,” Ettore wrote to Gentile on December 3, 1933. A hint of jealousy regarding the special relationship between Bohr and Heisenberg lingers in these words.

Ettore spent a short Easter break in Rome, going to Via Panisperna only a couple of times. He then returned to Leipzig, still in a good mood. On the train, he struck up a friendship with a drunk Neapolitan traveling to Germany to sell tomatoes. Ettore passed himself off as a fellow tomato seller, and the two became best mates for the duration of the trip. He arrived back in Leipzig in May of 1933, and for some time it was business as usual. And then something happened.

We simply don’t know what, but it triggered the beginning of a long slump into depression. After his uncharacteristic openness in the previous months, his dark side returned with a vengeance. He resumed his habit of walking on his own and rarely talked to anyone. His extreme negative criticism became worse than ever, alienating those around him. He became poignantly antisocial. During a conference, Heisenberg praised Ettore’s work and prompted him to intervene regarding a certain point of their theory; to everyone’s embarrassment, Ettore responded with silence. He rarely mentioned Heisenberg now in his letters home, and when he did, his enthusiasm was gone. His tone became brusque, rude, blatantly meant to shake off human contact. He wanted to be alone.

Why this sudden break in his humor? We simply don’t know, but he had followed a similar pattern before—for example, when he alternated gregarious happiness at Casina delle Rose with a more somber mood at Via Panisperna. But this time the swing was much more dramatic, and it would permanently damage his life. Are the roots of what happened in March 1938 to be found in May 1933? It’s possible, but what exactly happened?

We can only speculate, but I’m sure the chronology can never be so simply linear. Whatever happened in May 1933 must have been in part the culmination of the events of the past two years. Ettore had endured a war of attrition on many fronts, steadily fraying his nerves. He’d had to contend with the specter of a charred baby, in an affair that came to a head in 1932. He’d been trying to evade the stifling Majorana family atmosphere and the overwhelming presence of his mother. The quarreling at Via Panisperna, with its “negative energy,” had been getting worse: He’d been back there over Easter—we don’t know what happened, but his tone to the Boys, Gentile excepted—immediately changed. Lack of love and of a woman can’t have helped. And his health had finally given in to the bombardment of coffee and cigarettes. He may not have caught syphilis, as “suggested” by Segrè, but he did develop a bad ulcer while in Germany. Was this a cause of his troubles, or an effect?

Maybe it’s pointless to seek out a first cause. Perhaps the point is that there wasn’t one. Anyone can handle a single calamity; it’s usually the combined effect of many blows that topples even the strongest. And the maelstrom whisking Ettore into depression had been steadily upping its beat. Given the numerous upsets in his life, could Ettore have been a victim of the proverbial last straw?

Regardless, we can identify one event that hit Ettore hard in May 1933. Ettore may have been insensitive to publication and career accolades, but that doesn’t mean he didn’t care about his science. And it was around this time that he suffered a nasty blow. For he was in Leipzig when news began to arrive that his critique of Dirac’s theory, embodied in his 1932 masterpiece, was wrong.